This week, Benedict Bengioushuye Ayade, the governor of Nigeria’s Cross River State, will be in Guadalajara, Mexico taking part in the Governors’ Climate and Forests Task Force Annual Meeting. The aim of the GCF is to link states and provinces running REDD programmes with carbon markets in the rich countries.

This week, Benedict Bengioushuye Ayade, the governor of Nigeria’s Cross River State, will be in Guadalajara, Mexico taking part in the Governors’ Climate and Forests Task Force Annual Meeting. The aim of the GCF is to link states and provinces running REDD programmes with carbon markets in the rich countries.

But before getting carried away with the REDD promotion tour in Guadalajara, it’s worth taking a quick look at Ayade’s record so far in Cross River State.

In April 2015, Ayade won the election to become governor of Cross River State. He quickly announced a series of massive infrastructure projects in Cross River State. The Calabar Deep Seaport. The biggest garment factory in Africa. Several new cities. And a six-lane, 260-kilometre-long superhighway.

The superhighway through the forest

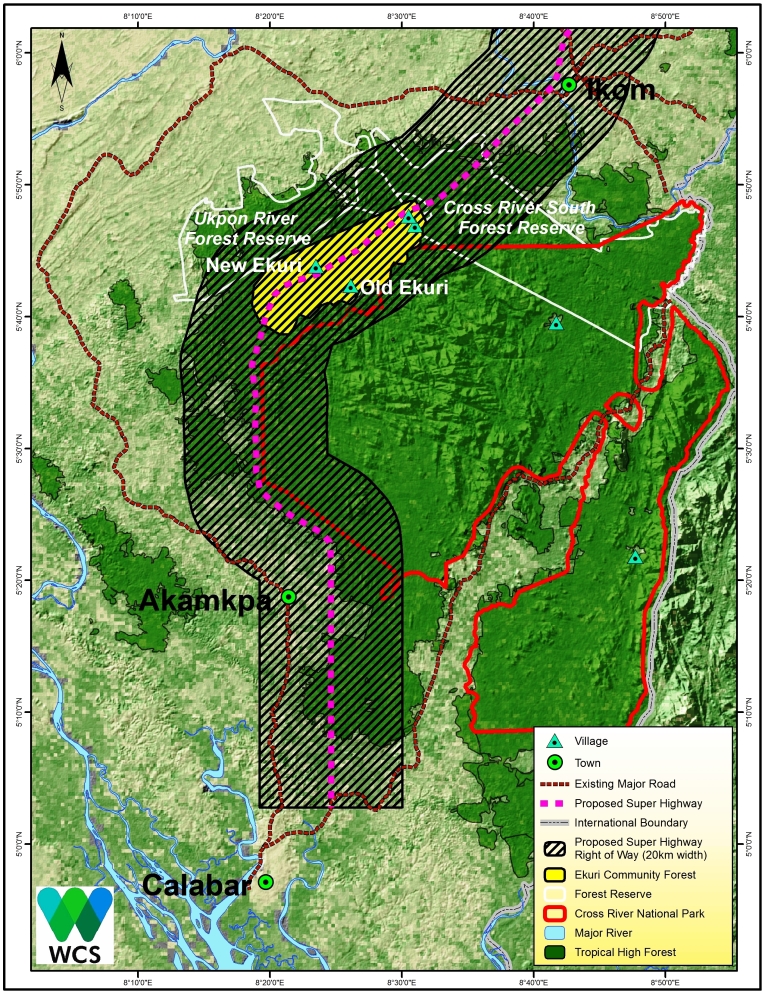

The superhighway is particularly controversial. Construction started in October 2015, before an environmental impact assessment had been carried out. After complaints from the National Park authorities, the route of the road was changed, to avoid going through the Cross River National Park. But large areas of forest remain under threat, including the Ekuri Community Forest.

The road would cost US$3.5 billion, but it is unclear where the money would come from. Little is known about the company building the road and the deep sea port, Broad Spectrum Industries Limited, apparently has no experience of road construction. The company may be based in Israel, Germany, or Port Harcourt, depending on which news report you’re reading.

On 22 January 2016, a Public Notice of Revocation was published in a local newspaper. It was signed by the Commissioner for Lands and Urban Development. The Notice stated that,

“all rights of occupancy existing or deemed to exist on all that piece of land or parcel of land lying and situate along the Super Highway from Esighi, Bakassi Local Government Government Area to Bekwarra Local Government Area of Cross River State covering a distance of 260km approximately and having an offset of 200m on either side of the centre line of the road and further 10km after the span of the Super Highway, excluding Government Reserves and public institutions are hereby revoked for overriding public purpose absolutely”.

Which would look something like this:

In March 2016, construction of the road was stopped, until an environmental impact assessment is carried out. While an EIA has now been carried out, Nigerian environmentalist Emmanuel Unaegbu writes that it is “inadequate and lacks merit”.

In June 2016, in a post on the Cross River Facebook page, Eval Asikong, an advisor to Ben Ayade, explained that “The Government is not claiming 10 km of land from both sides of the Super-Highway”. Instead, he explains that the “essence” of 20 kilometre wide strip, was for development control where house structures and every piece of land that is contiguous to the super highway is managed for development control and aesthetic value addition. Government does not forbid individuals from building around this perimeter but strongly frowns at indiscriminate building of structures. Besides, the state government intends to build new cities all along the super highway. Government can even paint structures within those areas for the dwellers as long as they adhere to the control measures. Government intent to provide commercial and social infrastructures like hotels, filling stations, etc to improve the environment.

The impacts of REDD in Cross River State

Meanwhile, Cross River State has started to implement REDD programmes that are having an impact on local communities’ livelihoods.

A report by the Nigerian NGO Social Action exposes the costs to forest communities. A task force in the Forestry Commission has a mandate “to enforce a moratorium on forest activities as part of the implementation process”.

Social Action reports that,

With neither adequate consultation nor alternative livelihoods options for communities, the task force has been harassing community members that have depended on the forests for generations. Movement and trade of products deemed to have been derived from the forests are confiscated. At Nwanga Ekoi in Akpabuyo Local Government Area (LGA) for instance, the task force routinely seizes agricultural products like kola nuts and fruits meant for the market on account that they are derived from forests earmarked for REDD + . The harvesting of Afang leaves, a local vegetable consumed in West and Central Africa, is now banned in affected forests. The hunting for bush meat, a main source of protein in the communities, as well as the tapping of palm wine from the raffia palm and associated brewing of kaikai, a local beverage, have been stopped.

In 2008, Liyel Imoke, then-governor of Cross River State, put in place a logging moratorium – a complete ban on wood cutting in all forests. In effect, forests that were under the control of communities have become forest reserves, under the control of the government.

The moratorium also includes harvesting leaves for food and medicine, and subsistence hunting. Bush meat was an important source of protein for forest communities.

Chief Owai Obio Arong of the Iko Esa Community told Social Action that

“I and my people have suffered for five years now since government stopped us from entering our forest because REDD is coming and till now I have not received anything from them.”

Ayade: “The conservation of forests is only a small aspect of the bigger picture”

On 24 August 2016, in a speech at a UN-REDD meeting, Governor Ayade argued that, “The conservation of forests is only a small aspect of the bigger picture”.

Ayade acknowledges that for eight years, forest communities have not been allowed to benefit from the forests.

Ayade demonstrates his ability to say what his audience wants to hear:

“UN-REDD plus is not about finances, it’s not about gross carbon stock, it’s not about monitoring the forests. It’s about social safeguards. It’s about livelihood security of the people.”

He got a round of applause for that.

He spoke “from his soul”, urging UN-REDD to move into the implementation phase:

“That implementation phase will address the pain and neglect, the harrowing poverty of our people, who for the last eight years have suffered a complete ban on their dependence on their forests. Who will now begin to see a legacy of hope.”

Perhaps predictably, he wants more money:

“I understand from statistics that reached us so far that you are proposing about US$12 million in your initial fees in the REDD-ready plus phase and we will move into the implementation phase. US$12 million is very exciting. But the relationship of pain and agony of our people in the last eight years, the relationship to the responsibilities ahead of us, it is very insignificant.”

He asks UN-REDD to focus on tree planting:

“There is a delicate balance between conservation and management. That is what I am asking for UN-REDD plus to focus as they move into the implementation phase. To focus agressively on tree planting. Because when you do, you increase the amount of rainfall. When you do, you reduce the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere.”

Then he talks about the green economy, the decarbonisation of Africa and the world, and about stopping using fossil fuels. He gets quite excited:

“Africa is challenged to seek alternatives for our crude oil. While Africa is struggling with that, Africa is also told, stop cutting your forests.

“Africa therefore is a whipping child. Standing before the world. We don’t have the technology for alternative research.”

At the end of his little speech, Ayade tells us that,

“The modalities and procedures, the validation process must focus on African philosophy of protection of the environment. It must be indigenous. It must be customised to reflect African heritage. Then a man who owns the forest, that pays from the forest, you only teach him how to depend on the forest without exploiting it to the detriment of the future.”

But of course Ayade made no mention of his proposed 260 kilometre-long superhighway in his speech

Source: REDD Monitor