Jun 2, 2016

By Chris Lang

REDD Monitor

In order for REDD projects to generate carbon credits, a “baseline scenario” has to be created. This is supposed to reflect what would have happened under business-as-usual, or what would have happened in the absence of the REDD project.

In order for REDD projects to generate carbon credits, a “baseline scenario” has to be created. This is supposed to reflect what would have happened under business-as-usual, or what would have happened in the absence of the REDD project.

The baseline is also necessary to show that the REDD project is additional, that the reduced emissions would not have happened without the project.

Conflicts of interest

Clearly, it is in the REDD project developers’ interest to have a baseline that predicts a high rate of deforestation in the project area. The higher the rate of deforestation in the baseline scenario the more carbon credits will be generated. And the less the project will have to reduce deforestation.

Of course REDD project developers can’t pick their own baselines and hope that the rest of the world believes they are not just making things up. The methodology proposed by the project developers has to be validated and project has to be audited. This is where voluntary certification schemes come in, like the Verified Carbon Standard, Plan Vivo, CarbonFix Standard, and so on.

But there’s a catch. The voluntary certification schemes make their money from generating carbon credits. The more carbon credits generated, the more money they make.

And the validators and auditors that are accredited by the certification scheme are paid directly by the project developers. In order not to lose future work opportunities, auditors are unlikely to be too picky about approving their clients’ methodologies.

This is a blatant conflict of interest at the heart of the REDD mechanism.

A new paper published in the International Forestry Review, looks at two REDD projects and asks a series of questions:

- What can we learn from the study of baseline settings in REDD+ projects?

- Does it sufficiently address the issues of permanence and additionality?

- More importantly, can certification standards provide a legitimate guarantee that chosen baselines are reliable measures for predicting CO 2 emissions’ reductions in the long term?

The paper is titled “The ‘virtual economy’ of REDD+ projects: does private certification of REDD+ projects ensure their environmental integrity?“, and the authors are Coline Seyller, Sébastien Desbureaux, Symphorien Ongolo, Alain Karsenty, Gabriela Simonet, Jean-François Faure, and Laura Brimont.

The two projects that the paper looks at are the Mai Ndombe REDD project in the Democratic Republic of Congo and the Corridor Ankeniheny-Zahamena REDD project in Madagascar. Both of these projects were certified under the VCS system, in 2012 and 2014, respectively.

The authors note that,

It is tempting for project developers to design a ‘convenient’ baseline scenario to generate more credits in order to seek financial profit or, as currently appears to be the most frequent case, to render a high-cost REDD+ project financially viable.

Mai Ndombe, DRC

The baseline for Mai Ndombe was established, not by looking at historical trends of deforestation in the project area and extrapolating into the future, but by using a reference area.

According to VCS guidelines the reference area does not have to be adjacent to the project area. In the case of Mai Ndombe, the reference area is about 600 kilometres away: the Mayombe forest in Bas-Congo province.

The authors point out that there are important differences between the two areas. Mai Ndombe is a dense, humid forest. Mayombe is a mosaic forest. Mai Ndombe is about 50% further from Kinshasa, the capital of DRC, than Mayombe. Mayombe is close to major shipping harbours. Bas-Congo province has a high population density. Mai Ndombe is sparsely inhabited.

The authors describe the reference area as “a dubious choice”.

The developer of the Mai Ndombe project, Wildlife Works, chose the following baseline scenario:

Where deforestation is initiated by the primary agent through legally-sanctioned commercial harvest and the area is ultimately converted to non-forest by the secondary agent through unplanned deforestation (e.g. subsistence agriculture)…

The authors question the assumption that in the absence of the REDD project, the forest would be logged (legally) and then converted to agriculture by local communities:

Ultimately, the loss of forest cover in DRC depends on many drivers including commercial or illegal logging, mining, farming and industrial agriculture. The weight of each driver on deforestation and forest degradation may reflect the degree of compliance with the law by logging/mining/agricultural companies, the local context of poverty and land tenure, and overall, the capacity of state bureaucracies to implement an efficient command and control system.

Corridor Ankeniheny-Zahamena, Madagascar

The CAZ project, set up by Conservation International, also uses a “questionable” reference area. The reference area in this case is 22 times the size of the project area.

Differences between the reference area and the project area include elevations and slopes, farming practices, and population density (the reference area is more densely populated than the project area). The authors conclude that, “there are major differences between the CAZ project area and its reference area.”

There are differences in the deforestation rates in the two area. The reference area has an annual deforestation rate between 1% and 1.26%. In the project area the annual rate is somewhere between 0.5% and 0.6%.

In its project design document, Conservation International takes the higher rate of deforestation for the reference area as a baseline scenario. And then assumes this same rate to be the historical rate of deforestation in the project area!

“The deforestation rate inside a well-established protected area is 0.20%/yr, being an 84% reduction of the historical deforestation rate within CAZ 1.26%/yr).”

The authors point out that without doing anything on the ground, Conservation International could, on paper at least, reduce deforestation by half. This, the authors note, with a hint of academic dryness, “could lead to the so-called ‘hot air’ phenomenon”.

Baselines are “untestable guesses”

Baselines allow project developers to put an exact figure on the number of tonnes of carbon that have not been emitted as a result of their project. But this number is based on a fiction.

There is no way of testing whether a baseline scenario is true or not, because it is something that might have happened had the REDD project not gone ahead.

As the authors conclude, “the baseline scenarios in REDD+ projects amount to untestable guesses”.

[W]ith REDD+ projects there is a kind of irreducible uncertainty regarding what the ‘right reference scenario’ should be. Our case studies show that only small differences in baseline scenarios – whether designed intentionally or not – can have severe financial (positive for business actors) and environmental (negative for the climate) consequences. The interest of the project developers is obvious: as the market price of carbon credits falls, the financial viability of a project (that relies on the carbon market for financing) declines. ‘Optimizing’ the parameters, notably those related to baseline settings, seems to be the only way to maintain the viability of a project’s business model.

The authors of the paper are careful to talk about project developers “optimizing the parameters” or using a “convenient baseline scenario”.

Fraud would be a better way of describing what REDD project developers are doing when they set bogus baselines. The voluntary certification systems, such as VCS, are complicit in this fraud.

Nov 30, 2015

via New Internationalist Magazine

The climate negotiations have done worse than nothing to prevent climate change. Nigerian activist Adesuwa Uwagie-Ero takes us on a historical journey, and suggests some ways to shift the international process onto a path toward climate justice.

As governments from more than 190 nations prepare to gather in Paris to discuss a new global agreement on climate change, Nigeria is still battling with fundamental problems. These include increasing poverty levels of citizens, floods, gas flaring in the South, increased threat of desertification in the North, lack of sector coordination, and a population explosion. All these have direct implications for our food supply systems, water scarcity and health.

The sorry state of the Nigerian environment is best seen through the lens of the impacts of the oil and gas sector. A United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP) assessment documented the level of ecocide inflicted on the Ogoni environment over 50 years of reckless exploitation. UNEP surmised that it will require about three decades of work to detoxify the Ogoni environment, where active oil extraction was shut down in 1993.

Four years after the launch of that report, little has been done about this clear ecological emergency. Only recently has the Buhari-led Nigerian administration committed the sum of $10 million to the clean-up. It is time to place the ecological question at the heart of our political debates and action plans. We are the people of the environment: our lives, culture and production are embedded and intertwined with nature.

The powerful browbeat the weak

Current commitments on greenhouse gas emission cuts will run out in 2020, so in Paris governments are expected to produce an agreement on what happens for the next decade, and potentially beyond. The optimism that fossil fuels will remain the dominant energy source into the foreseeable future is delusory and not founded in fact. The world may ramp up extreme extraction such as fracking, but that will not stop the shift away from climate-changing fossil fuels occurring.

As the exploitation of nature reaches the zenith of unreasonableness, traders are now seeing nature as an object for speculation and wholesale commodification. Good concepts such as sustainable development are being turned on their heads. The concept of ‘Green Economy’ on which even the brownest sectors cling turns out to be a platform for insisting that nature cannot be defended. It must be assigned a monetary value; its intrinsic value is absolutely ignored.

The conferences of parties (COP) to the climate change convention have over the years turned into sessions where the powerful browbeat the weak and efforts are made to avoid responsibility and to act in narrow national or regional interest.

The rapid slide down this slope took root at COP15 in Copenhagen. It was deepened at COP16 in Cancun where the concept of ‘consensus’ got redefined as ‘agreement by the majority’.

COP17 in Durban took the medal as the conference whose critical achievement was the blatant postponement of action while the earth burns. Nations like the US, Canada, Japan and Australia openly throw spanners in the works. Some go as far as foreclosing any participation in legal and accountability formats.

COP18 at Doha was a sigh, as leaders kicked the noisy decision-making can further down the road. In the negotiations following Doha, the talks in Bonn and Geneva continued to show the strains between developed, emerging economies and differently developed nations – especially with regard to emissions reductions commitments and mitigation actions.

At the negotiations held in May 2013 at Geneva the developed countries pushed for a legally binding ‘spectrum of commitments’ from both developed and developing countries. However, their stance was based on targets determined by each government according to their national capabilities and circumstances – not by what science requires. They suggested that these would be reviewed periodically, with the aim of keeping global temperature rise in line with the 2 degree Celsius goal.

These trends leave us with the burning question: has the COP process really helped the world tackle climate change?

Carbon colonialism

Climate change has become big business, and false solutions are celebrated. Whereas it has been clear for a long time now that global warming is mostly man-made and is due to the huge amount of greenhouse gases pumped into the atmosphere by polluting activities involving the use of fossil fuels, preferred actions taken by nations and industries have been patently false actions.

These actions are mostly predicated on the specious notion of carbon offsetting. The notion itself is built on the creed that financial markets hold the key to solving humankind’s problems.

Carbon was first placed on the market at the Kyoto COP in 1997. It means polluters can keep polluting, provided they pay for it in cash (a carbon tax) or imagine that some trees somewhere else in the world are absorbing an equivalent amount of carbon as they are emitting. Polluters perform acts of indulgence through offsets.

The Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) covers some such offset schemes, where projects that help reduce carbon emissions earn carbon credits. Some really obnoxious projects get listed under the CDM.

Gas-to-power projects utilizing gas that would otherwise be flared seem to make sense, except that gas flaring has been illegal in Nigeria since 1984. There has also been a High Court ruling against Shell over its gas flares at Iwerekhan, Delta State. The court ruled that gas flaring is illegal, unconstitutional and an affront to people’s rights. That judgment was delivered in November 2005 but the flares continue to roar.

Projects that qualify for the CDM are expected to be ones that bring in ‘additionality’. But Nnimmo Bassey, former Executive Director of Environmental Rights Action, makes the point that ‘any compensation for such an activity flies in the face of reason. Gas flares are the most cynical manifestations of corporate insolence in the face of climate change and environmental health. The flares release greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous and sulphur oxides with other harmful substances that greatly affect human health.’ Just when we thought we had overcome slavery we are getting dragged into not just carbon colonialism, but carbon slavery.

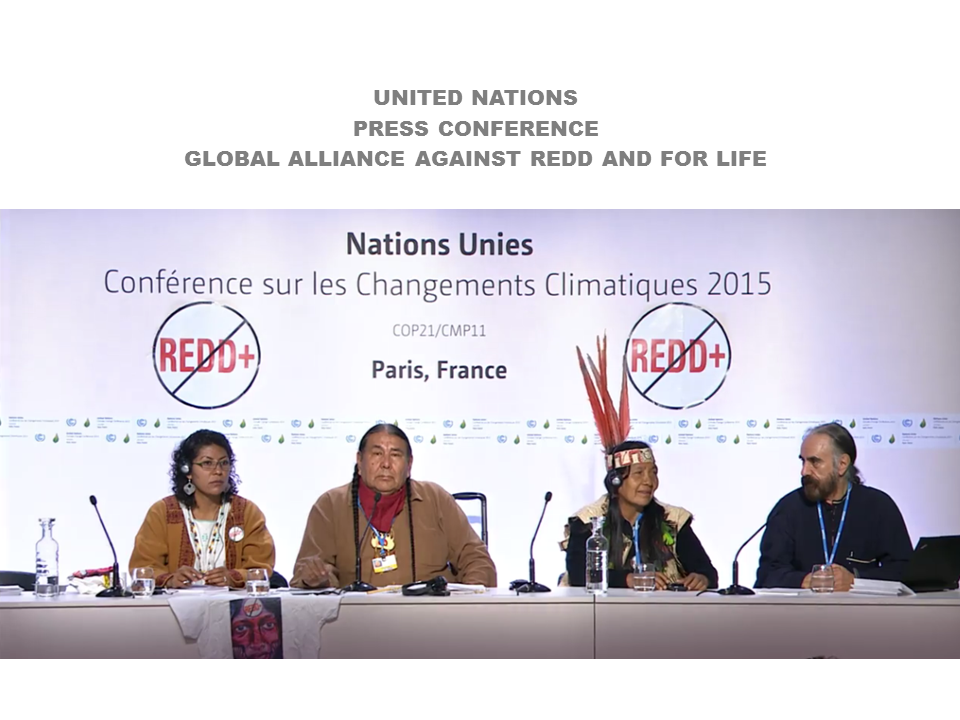

Seeing REDD

Market mechanisms threw Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and forest Degradation (REDD) into the ring at the Bali climate meeting of 2009. REDD and its variants allow polluters to keep on at their business of polluting while ‘showing’ that trees in a forest or plantation elsewhere absorb the carbon they emit. Thus REDD projects permit pollution and cannot be said to reduce emissions. The name itself is a sad joke: REDD does not stop deforestation, but at best defers or displaces it. A REDD scheme is a business scheme, pure and simple.

A declaration from the Climate Space at the Tunis World Social Forum in March 2013 insisted ‘we cannot put the future of nature and humanity in the hands of financial speculative mechanisms like carbon trading and REDD. REDD, like Clean Development Mechanisms, is not a solution to climate change and is a new form of colonialism. In defence of Indigenous Peoples, local communities and the environment, we reject REDD+ and the grabbing of the forests, farmlands, soils, mangroves, marine algae and oceans of the world, which act as sponges for greenhouse gas pollution…’

No REDD in Africa Network (NRAN) recalls a situation in Mozambique, where a study found that thousands of farmers in the N’hambita REDD project were paid meagre amounts for seven years for tending trees. ‘Because the contract is for 99 years, if the farmer dies his or her children and their children must tend the trees without any further pay or compensation. This has been interpreted as a clear case of carbon slavery.’

Agrofuels and technofixes

Another false solution has been the presentation of agrofuels as a replacement of fossil fuels, when in fact it keeps the fossil fuels paradigm and is equally polluting. Moreover, it has triggered massive land-grabs. Even at its peak agrofuels cannot replace fossil fuels because the amount of land needed to cultivate crops and the feedstock needed for production is simply not available on planet Earth.

Geo-engineering and agricultural genetic engineering are other false solutions that lull humans into thinking that they can keep current polluting lifestyles and find techno-fixes for their addiction.

Criteria for climate justice

So what must be done? Time is ticking fast, the peoples of the world must continually press for climate justice, understanding that no nation, rich or poor, is immune to the challenges posed by global warming. Reflections on the challenge can leave us utterly exasperated, considering the corporate capture of governments and the refusal of states to take actions that would benefit the people and the planet, and not just the corporations.

This has been amply illustrated by the tragic weather events that have fairly democratically impacted nations around the world. These effects are undeniable: sea-levels are rising, Arctic ice is melting and may lead to changes in ocean circulation, sea-surface temperatures are rising, sea water is acidifying, due to an increase of dissolved carbon dioxide, we are seeing a heavier rainfall pattern, hurricanes and floods, emerging crop diseases and crop failures, intense droughts and desertification, to mention just a few impacts. These negatively affect human lives and that of other species.

Urgent actions are needed across the globe. These include:

Urgent actions are needed across the globe. These include:

Rapid transition from dependence on fossil fuels – including in transportation, power generation and agriculture;

A just global climate treaty that recognises historical responsibility, climate debt and the need for legally binding emissions reduction;

Elimination of market mechanisms (including CDM, REDD, REDD+) and all other false solutions from the climate regime;

Recycling of waste and reducing consumption in line with planetary limits;

National laws that build mechanisms for climate mitigation and adaptation actions, including coastal protection and combating desertification;

Stop gas flaring in the Niger Delta and at Badagary communities in Nigeria immediately;

Stop fracking and other extreme extraction, including drilling in the Arctic region;

Educate grassroots communities and the creation of community climate defence committees that would set rules for physical developments as well as monitor impacts of climate change;

Universal respect of Mother Earth’s rights as articulated at the Cochabamba People’s Summit on Climate Change;

Leave the fossil fuels in the soil. Besides global warming, the environmental cost of fossil fuels cannot justify a continued reliance on the resource. Reflect on Shell’s pollution of Ogoni land. Think about the open scars created by tar sand extraction in Alberta.

Awake, arise, mobilize!

Our narrative must be the story of our lives, told by us and dipped in our experiences. As Arundhati Roy puts it, ‘If there is any hope for the world at all, it does not live in climate change conference rooms or in cities with tall buildings. It lives low to the ground, with its arms around the people who go to battle every day to protect their forests, their mountains and their rivers because they know that the forests, the mountains and the rivers protect them and are their source of livelihood.

The first step toward re-imagining a world gone terribly wrong would be to stop the annihilation of those who have a different imagination – an imagination that is outside capitalism as well as communism. An imagination which has an altogether different understanding of what constitutes happiness and fulfilment.’

It is our life. We know how the rain has beaten us and for how long. Indeed we did not inherit the Earth; we borrowed it from our children.

Our narrative must not be stuck in the crisis narrative imagined by others. We must awake, arise, mobilize and work for the transformation of our society and planet – by all legitimate means available and necessary.

Adesuwa Uwagie-Ero is a campaigner with Environmental Rights Action in Nigeria.

– See more at: http://newint.org/features/web-exclusive/2015/11/26/escaping-carbon-slavery-the-view-from-nigeria/#sthash.9KE6lqfu.dpuf